On Purpose: 3 questions you should ask yourself to find meaning at work

Do I like who I am becoming at work? Do I have a clear sense of what is right and what is wrong? Does the work we are doing make me feel hopeful for the future?¹

Whether you are an employee wondering if your current work is meaningful or a manager unsure of whether your team identifies with your company’s purpose, posing these questions may help you gain some clarity. In this article you will learn how meaningful work can be defined and promoted at work.

The search for a higher meaning and sense of purpose is inherent to the human experience and the answers we find, or fail to find, majorly contribute to our overall outlook and contentment in life. Our professional lives are not exempt from this pursuit. In 2020 workers in the U.S. spent a daily average of about 7.5 hours at work.² In the same year, the expected average duration of working life for workers in the EU reached 37.7 years.³ Given the large amount of time people dedicate to their jobs every day, most days of the year, finding meaning in one’s behaviours and actions at work may be among the most important sources of meaning in life overall.⁴

On a more proximal level, meaningful work is associated with:

Thus, both on an individual as well as an organisational level, fostering meaningful work is highly desirable.

What makes work meaningful?

The desire to increase the sense of meaning associated with work is reflected in a growing body of research dedicated to the investigation of meaningful work as a construct and ways to enhance its manifestation in practical work environments.

Meaningful work is commonly characterised by

- the subjective experience of purpose and significance,

- the alignment of work with the meaning and purpose of one’s life in general and

- the perception of meaningful contribution through applied efforts, the effects of which transcend the individualistic realm of self.⁶

Lips-Wiersma and Wright (2012) differentiate between four dimensions of meaningful work, namely developing the inner self, unity with others, service to others and expressing full potential. These aspects of meaningful work can be further categorised between the antipodes of self and other, being and doing as well as inspiration and reality¹ (see figure 1).

Accordingly, meaningful work is established through multiple factors and requires balance between the desire to meet one’s own needs and the needs of others, between reflection and taking action as well as between broader exploration and a focus on factuality:

Figure 1. Based on the figure “Framework of meaningful work” by Lips-Wiersma & Wright (2012)¹, p.660

How to foster meaningful work?

In the scope of their literature review, Lysova, Allan, Dik, Duffy and Steger (2019)⁷ conclude that organisations may foster meaningful work by creating high quality jobs which are well-designed, fit the employee and allow for job crafting. Furthermore, meaningful work may be enhanced through facilitative leaders and a work environment with positive culture and relationships as well as access to decent work. The authors suggest that decent work, which meets basic human needs of survival, social connection and self-determination, serves as a prerequisite for the higher pursuit of meaningfulness and go on to highlight the importance of societal incentives to create according work environments.

Societal systems, the jobs within it and their perceived value are ever-evolving and can be redesigned in the pursuit of growth and optimal adaption to environmental circumstances.

This became especially apparent in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, which imposed a re-evaluation of professions of high systemic importance, e.g in the health care sector or the food distribution industry. Suddenly, professions with a high proximal impact appeared elevated, sparking discussions around the appropriateness of low wages and common lack of social recognition. The crisis highlighted the persisting stigma and prejudice associated with certain jobs and how these perceptions can evolve in accordance with changing circumstances.

Capture of one of the recurring tributes to hospital staff (NHS) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/12/world/europe/coronavirus-nhs-uk.html

Accordingly, Ashforth and Kreiner (1999)⁸ describe three ways to change the perceived meaning of stigmatised work by establishing new attributions: Reconceptualisation, Recalibration and Refocusing.

- Reconceptualisation of work involves the consideration of the overarching occupational goal and the positive value associated with it.

- Recalibration entails the revision of the scale by which the relative value and valence of work is measured. As a consequence, aspects of work that normally receive little attention may be seen as more valuable and a larger component of the job.

- Refocusing describes a shift of attention towards aspects of work that are socially recognised rather than tasks that may be deemed socially stigmatised.

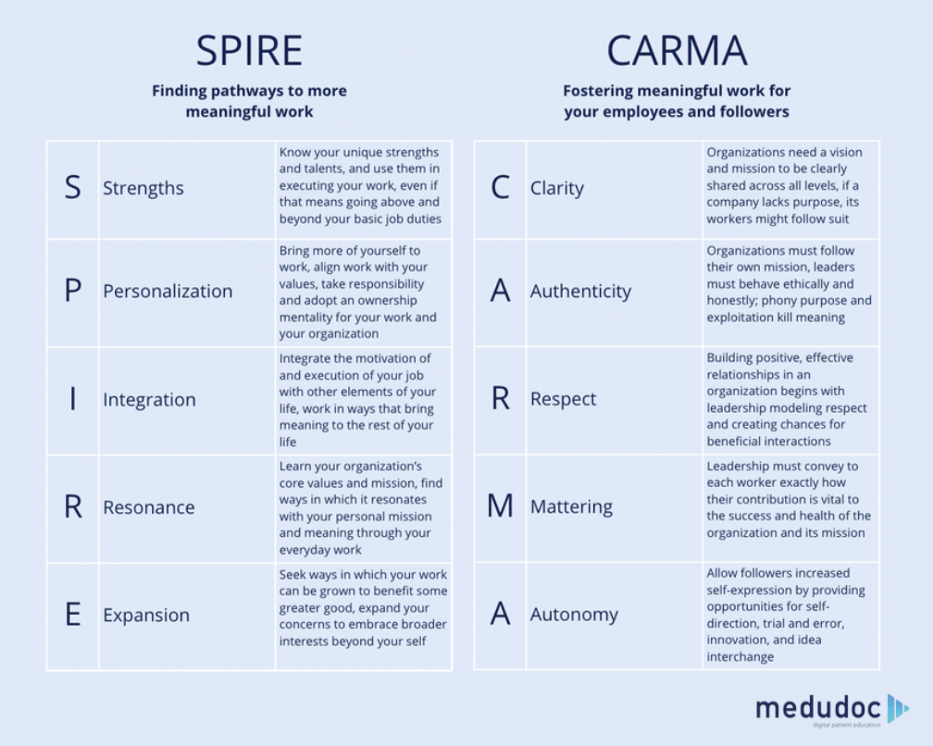

Dik, Duffy and Eldridge (2009)⁴ propose another approach by stating that meaningful work may be enhanced by identifying unique strengths and applying them regularly. This idea is also represented in the pathway to meaningful work suggested by Steger (2016)⁶. Taking both person- and organisation-level factors into consideration, the author proposes five respective principles individuals and organisations can apply to craft and foster meaningful work (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Based on the depiction of the SPIRE and CARMA model by Steger (2016)⁶, p. 74

Automated work: More replaceable and less meaningful?

In recent years, brisk developments in technology have led to major changes in the ways modern work is organised and structured. Given the advancing replacement of human resources through technology and automation, fostering meaningful work may become more and more difficult in many professional areas.

The recent media attention around AI-equipped cameras installed in some of Amazon’s delivery vans exemplifies this clearly. The novel technology, which detects safety violations and is programmed to alert the driver accordingly, has been met with scepticism regarding the protection of employees’ privacy.⁹ While the establishment of such highly technology-assisted work environments may hold great benefits in terms of increased safety and heightened performance, they also represent yet another step towards a working world in which employees are progressively stripped of their responsibilities and autonomy.

Given the impact of meaningful work on various aspects of well-being and psychological distress (e.g. depression)⁵, a loss of meaningfulness in the face of workers’ replacement by technological solutions may have serious implications in terms of occupational well-being and overall mental health.

While a comprehensive evaluation of the current development towards a highly technological working world should highlight the potential risks of rapid automation, the huge potential of shifting human resources from mundane tasks to perhaps much more fulfilling, meaningful work should not be disregarded.

How medudoc utilises technology to improve doctors’ and patients’ lives

At medudoc, we are striving for an innovative digitisation of patient education processes through means of audiovisual education material.

By automating highly repetitive tasks which do not require health care professionals’ individual attention, we aim to alleviate heavy workloads, increase time efficiency and therefore create the opportunity for doctors to focus on meaningful, personalised patient education.

Rather than replacing the individual doctor-patient communication through technology or restricting doctors in their autonomy, medudoc

enables physicians to focus on aspects of their profession that truly require and emphasise their unique abilities.

How we continue to find meaning in our own work at medudoc

We believe that living our core values, in the sense of deriving direct implications for our behaviours and actions on an individual as well as a wider organisational level, will enable us to fulfil our purpose. Therefore, by fostering education, collaboration, trust, care, empowerment, assertiveness, inclusion and open-mindedness, the medudoc team strives to improve healthcare through innovative patient education.

Only by establishing a strong sense of who we are and what we stand for, can we adequately address the question of why we exist as a company and subsequently put actions into motion to fulfil that purpose.

To pursue a purpose without assessing the degree of congruence with one’s values and beliefs leads to a lack of motivation at best and a complete sense of inauthenticity or lack of integrity at worst. Therefore the alignment between individual and organisational values, beliefs and purposes requires a high degree of introspection which is encouraged at medudoc from the very first touchpoint with the company. Aside from a person-centred and value-driven hiring process, medudoc fosters this alignment by offering a guide on purpose and self development as part of the company’s personal development and feedback processes. Regular employee satisfaction surveys are set up to keep an open dialogue regarding the team’s connection to the shared company values. Sustained open communication ensures that each and every member of medudoc can identify with their work, continues to find meaning in it and is given the tools to find satisfying answers to the questions …

- Do I like who I am becoming at work?

- Do I have a clear sense of what is right and what is wrong?

- Does the work we are doing make me feel hopeful for the future?

If these questions have inspired you, too, to look for a bigger professional purpose, we hope this article has given you some useful ideas on where to start your own personal journey to meaningful work. As the model proposed by Steger (2016)⁶ suggests, both employees and managers play an important role in fostering meaningful work. So reach out to your team, colleagues or manager and start the conversation!

About the author:

Evelyn Lange works as a Medical Education Writer at the digital health start-up “medudoc” in Berlin. With a background in psychology she is now working on bridging the digital gap between doctors and patients through the creation of intelligible medical education content.

References:

¹Lips-Wiersma, M., & Wright, S. (2012). Measuring the meaning of meaningful work: Development and validation of the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale (CMWS). Group & Organization Management, 37(5), 655–685.

²Bureau of Labour Statistics — U.S. Department of Labor. (2021). AMERICAN TIME USE SURVEY — MAY TO DECEMBER 2019 AND 2020 RESULTS. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/atus.pdf

³Eurostat Statistics Explained. (2021). Duration of working life — statistics. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Duration_of_working_life_-_statistics#Evolution_of_the_duration_of_working_life_over_time:_2000-2020

⁴Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Eldridge, B. M. (2009). Calling and vocation in career counseling: Recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(6), 625.

⁵Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337.

⁶Steger, M. F. (2016). Creating meaning and purpose at work. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of the psychology of positivity and strengths‐based approaches at work, 60–81.

⁷Lysova, E.I., Allan, B.A., Dik, B.J., Duffy, R.D., & Steger, M.F. (2019). Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 374–389.

⁸Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (1999). “How can you do it?”: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Academy of management Review, 24(3), 413–434.

⁹Palmer, A. (2021). Amazon is using AI-equipped cameras in delivery vans and some drivers are concerned about privacy. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/02/03/amazon-using-ai-equipped-cameras-in-delivery-vans.html